Summary

The business world is changing rapidly, new risks continue to emerge at a faster pace than has been seen in the past while existing risks are also evolved. To compactandbringmorevalueindealingwithrisks, the Committeeof Sponsoring Organisations of the Treadway Commission (COSO) has updated its most widely recognised risk management frameworks - COSO ERM 2004. The newly introduced framework, COSO Enterprise Risk Management - Integrating with Strategy and Performance (COSO - ERM 2017), aims to provide companies with a more robust approach to managing risks, which helps to create, preserve and realise value of the companies.

Oil and gas is one of the highest risk and capital-intensive industries facing many uncertainties around exploration, extraction, distribution, volatile commodity prices and the perplexing political landscape. Therefore, a discipline and systematic approach for risk managementisneededforoilandgascompaniestoidentify, assess, manageandmonitorrisks, and COSOERMprovidesariskmanagement framework to do so. Oil and gas companies are also in the forefront to adopt many technologies such as robotics, digitisation, and the Internet of Things (IoT) intotheoperationalenvironment. Asaresult, cyber risk becomesincreasinglyimportantforoilandgascompanies to respond to.

Key words: Enterprise risk management, cyber risk.

1. COSO ERM 2017

Enterprise risk management (ERM) has attracted much attention in the last several years, particularly following the great global financial crisis. In today’s uncertain world of complex and interrelated risks, an increasing number of organisations have implemented or are developing an ERM system as an enabler to deliver their strategies and achieve their objectives.

However, gaps remain in using risk as a value creator. According to a Deloitte global survey in 2017 with over 300 board members and C-suite executives of companies from USD 1 billion in revenue and up, operating in various industries in the Americas, EMEA and Asia/Pacific regions, nearly 9 out of 10 organisations recognise that risk management should focus on value creation - not mere risk avoidance. But fewer than 20% are taking sufficient action in this regard.

Along with many available risk management frameworks such as COSO Enterprise Risk Management - Integrated Framework(2004), ISO 31000 Risk Management (2009) - Principles and Guidelines on Implementation, BS 31100 Code of Practice for Risk Management, FERMA A Risk Management Standard and OCEG Red Book 2.0 (GRC Capability Model), COSO Enterprise Risk Management - Integrating with Strategy and Performance (COSO - ERM 2017) was introduced in 2017 and distinguished itself from other risk management approaches by its emphasis on the connections between risk, strategy and value.

Traditionally, the key driver for enterprise risk management (ERM) implementation is to protect value of the organisation and the focus is mostly to reduce the risk impact and risk functions tasked with identifying threats to the organisation’s business objectives or strategies. In many organisations, risk is an important, but largely supportive function focused on well-defined risks such as strategic, financial, operational and cyber risk, yet rarely integrated with the core business. This can create a gap of considering of risks in decision making process.

The right risk management should be embedded in management’s business processes, where identifying and managing risks are integral parts of decision making process. This level of integration can help organisation achieve intended business objectives more effectively and get better value from its ERM program. The new ERM framework is focused on the relationship between risk and value and the important role of ERM in creating, preserving, and realising value. It helps an organisation exploring new opportunities by taking acceptable risks and realising the value of taking these risks.

There are also advantages to enhance ERM with a strategic risk approach by embedding risk into strategic planning process. This will help organisation to consider alternative strategies according to organisation’s risk appetite. It also improves the resilience of the company’s strategy and helps to address barriers to execution; encompasses activities to prepare for and respond to novel crises; covers the spectrum of risks, from high- level strategic risks that affecting all business units to the operational risks managed at the department level; links risk data at different levels, allows reallocation of resources to the organisation’s top risks and embeds risk management into existing organisational processes.

2. Risks in oil and gas industry

Organisations in virtually industry and country are reminded frequently that they operate in a risky world. As a capital-intensive industry, oil and gas is not an exception. Risk is a characteristic of oil and gas business, as a part of fundamentals. Below are some common risks in oil and gas industry:

Political risk - An oil and gas company is covered by a range of regulations that limit where, when and how extraction is done, which differ from state to state. Political risk generally increases when oil and gas companies are working on deposits abroad. Numerous issues may arise from this, including sudden nationalisation and/or shifting political winds that change the regulatory environment. Depending on what country the oil is being extracted from, the deal a company starts with is not always the deal it ends up with, as the government may change its mind after the capital is invested, in order to take more profit for itself or for some other political reasons. An important approach that a company takes in mitigating this risk includes careful analysis and building sustainable relationships with international oil and gas partners - if it hopes to remain in business for the long run.

Geological risk - Many of the easy-to-get oil and gas is already tapped out, or in the process of being tapped out. Exploration has moved on to areas that involve drilling in less friendly environments, such as on a platform in the middle of an undulating ocean. There is a wide variety of unconventional oil and gas extraction techniques that have helped squeeze out resources in areas where it would have otherwise been impossible. Geological risk refers to both the difficulty of extraction and the possibility that the accessible reserves in any deposit will be smaller than estimated.

Price risk - Beyond the geological risk, the price of oil and gas is the primary factor in deciding whether a reserve is economically feasible. Basically, the higher the geological barriers to easy extraction, the more price risk a given project faces. This is because unconventional extraction usually costs more than a vertical drill down to a deposit. This does not mean that oil and gas companies automatically cease operations on a project that becomes unprofitable due to a price dip. Often, these projects cannot be quickly shut down and then restarted. Instead, oil and gas companies attempt to forecast the likely prices over the term of the project in order to decide whether to begin. Once a project has begun, price risk is a constant companion.

Supply and demand risks - Supply and demand shocks are a very real risk for oil and gas companies. As mentioned above, operations take a lot of capital and time to get going, and they are not easy to shut down when prices go south or to ramp up when they go north. The uneven nature of production is part of what makes the price of oil and gas so volatile. Other economic factors also play into this, as financial crises and macroeconomic factors can dry up capital or otherwise affect the industry independently of the usual price risks.

3. Cyber risk

Theoilandgasindustryismovingintothenextstageof evolution, whereby robotics, digitisation, and the Internet of Things (IoT) are rapidly being integrated into the operational environment. The interest of cyber criminals in industrial operations has increased over the last decade resulting in cyberattacks that have compromised both production and safety. These attacks have made cyber security a hot discussion topic in boardrooms around the world, and now, a growing number of organisations are developing large transformation programmes to address these new operational threats.

On 30 March 2018, various major U.S. pipelines across the US reported data system blackouts after a third-party electronic communication system was attacked. That electronic data interchange (EDI) system, which was identified as Energy Services Group’s Latitude Technologies Unit, controls computer-to-computer document exchanges with customers. The Energy Services Group provides the system to more than 100 natural gas pipelines, energy marketers and utilities nationally.

The EDI cyberattack led to the shutdown of the communication systems for several pipelines utilising those services, including that of Dallas, Texas - based Energy Transfer Partners - a U.S. Fortune 500 natural gas and propane company owning more than 71,000 miles of pipelines containing natural gas, crude oil and other commodities.

Although the incident is presumed to have been focused on gaining pricing information for competitive advantage as opposed to disruption of the pipelines, experts are stressing the importance of securing third-party systems in supervisory control and data acquisition (SCADA) environments. There is a critical need that all supply chain network providers that connect to the companies’ assets be held to the same high security standards. Fred Kneip, CEO of CyberGRX, said that it does not matter how well an organisation protects its own perimeter if third parties with weak security controls create vulnerabilities that can be easily exploited.

However, making operational processes secure, vigilant and resilient is a challenge as this requires the organisation to harmonise and align two cultures, engineering and IT. In addition, the operational environment demands tailored technical solutions that are not always easy to secure. Solving these challenges requires a clear understanding of both the engineering and IT disciplines as well as leading sector specific cyber security practices.

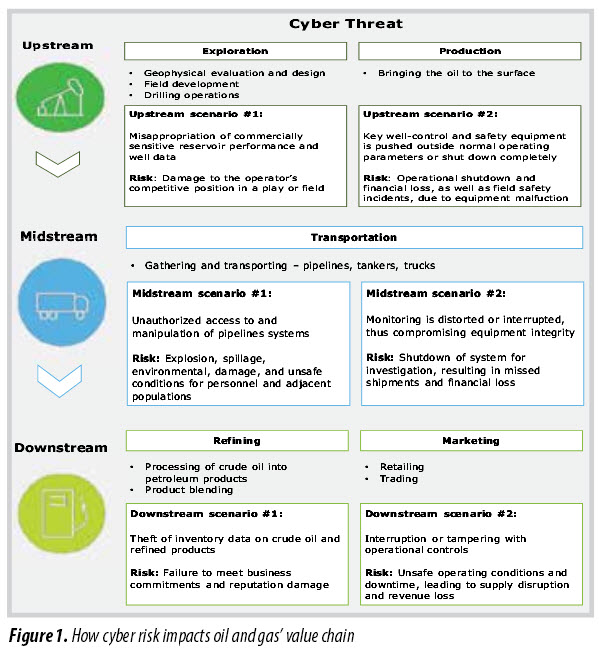

Consider the following scenarios, the possibility of which did not exist a few years ago:

• Insecure remote access communication allows a cyber-criminal to hijack a process control system and push production to unsafe levels.

• Poor security practices by a third party contractor allow a virus to migrate into the production environment, shutting down critical Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA) systems and creating unsafe working conditions.

• Improper testing of IT systems prior to deployment results in a system crash, leading to disruption or shutdown of operations.

• Technology acquired directly by a facility, without adequate testing and evaluation, goes unpatched and introduces a vulnerability which allows members of an adversarial community to gain remote access to programmable logic controllers (PLC), thus giving them the ability to disrupt the production process at will.

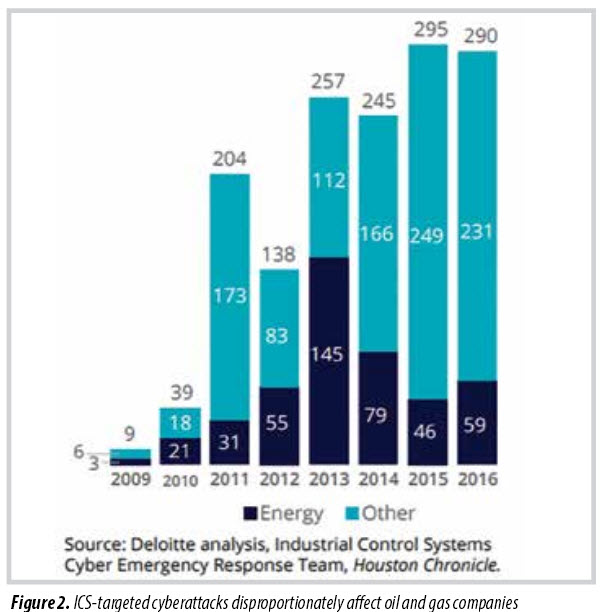

This concern is not just academic: Hackers have initiated hundreds of cybersecurity incidents targeting US oil and gas control systems (Figure 2), many with significant real-world impacts.

Organisations have no alternative options but to be proactive in combating cyber risk.

Conduct a maturity assessment - Once the risks are understood, an oil and gas company should assess the maturity of its cyber security controls in an operational environment. While not every risk can be mitigated, it is important to know what type of controls are in place and where to focus improvement efforts. This means giving appropriate consideration to how potential security breaches within Industrial Control System (ICS) link to business risks. Importantly, this can not be done by an engineering or IT group independently; it requires a multi disciplinary team of business, operations, engineering, and IT security professionals.

Build a unified programme - Although building and implementing a program of this nature is a multi year, transformational effort, each phase of the initiative should have the same objective in mind, moving up the maturity scale to create an ICS environment that is secure, resilient, and vigilant.

Implement key controls - Including awareness training, access control, network security, portable media, incident response.

Embrace good governance - Clear ownership of ICS security is crucial, and roles and responsibilities should be clearly defined for everyone involved, from managers to process operators to third parties. Ultimately, there must be a single line of accountability. Without one, it is challenging not only to define requirements that apply to the whole organisation but also to identify where centralised versus local solutions are appropriate.

4. Conclusions

In the past few years, the oil and gas industry has seen the traditional boundaries between corporate IT and ICS largely disappear. Today, the evolution continues with the digitisation of the oil and gas field. Apart from the traditional risks that the oil and gas industry has faced up for decades, as this interconnectedness marches on, so does the frequency and sophistication of cyber- attacks. However, most companies have not kept pace in terms of their preparedness. The place to start is assessing the maturity of the cyber security controls environment. Going beyond traditional operational safety considerations to implement a secure, vigilant, and resilient programme is not only essential for enhancing an oil and gas company’s ability to protect operational integrity amid a growing range of cyber threats, but also to achieve operational excellence by taking advantage of the productivity benefits offered by a digitised, fully integrated ICS environment.

In summary, boards of directors and senior executives at oil and gas companies cannot afford to manage risks reactively, especially in light of the speed of change in the industry that could accelerate beyond the current velocity. That the energy world is changing is not up for debate. The real question is: How fast can energy companies adapt to the speed of change and prepare for the unexpected?

References

1. Andrew Slaughter, Paul Zonneveld, Thomas Shattuck. Refining at risk. Securing downstream assets from cybersecurity threats. Deloitte. 2017.

2. Mary E.Galligan, Kelly Rau. COSO in the cyber age. Deloitte Global. 2015.

3. Paul Zonneveld, Andrew Slaughter. An integrated approach to combat cyber risk: Securing industrial operations in oil and gas. Deloitte Global. 2017.

4. Deloitte Global. Taking aim at value survey: Avoid overconfidence and look again at risk. 2017.

5. Deloitte Global. COSO’s ERM framework update comes with strategic risk advantage. 2017.

6. Deloitte Global. 2017 oil and gas industry executive survey: Trends show a pause in industry confidence. 2017.

7. Lindsey O’Donnell. Insecure SCADA system blamed in rash of pipeline data network attacks. 2018.

8. Naureen S.Malik, Ryan Collins, Meenal Vamburkar. Cyberattack pings data systems of at least four gas networks. Bloomberg. 2018.